The New Love:

"When the Arts & Crafts

castrated William Morris"

My body knows unheard-of songs

“Imagine a King or a Judge, a stupid fat guy.

The moment he puts on the insignia of power,

all of a sudden there is an aura of power...”

Between a simple individual and an external element (the uniform, crown, insignia) which confers power, there is a gap.

A magical object, imbued with symbolic meaning, is never fixed to a bearer - it is independent and flighty. There is gap between king and crown: a gap which generations of women drew attention to as they corrected and redirected William Morris’s discourse and movement, changing their trajectories. A language that may have begun in bohemian men’s socialist clubs (and echo chambers) was transformed into an international vehicle for the empowerment and liberation of working women. New characters flooded the Victorian “language of men and their grammar” which would help bring to woman “their meaning in history”. (Cixous, 1976)

So this will be a women’s story, as well it should be... but from the very beginning of the Arts and Crafts movement it always and already was.

Men just didn’t know it yet!

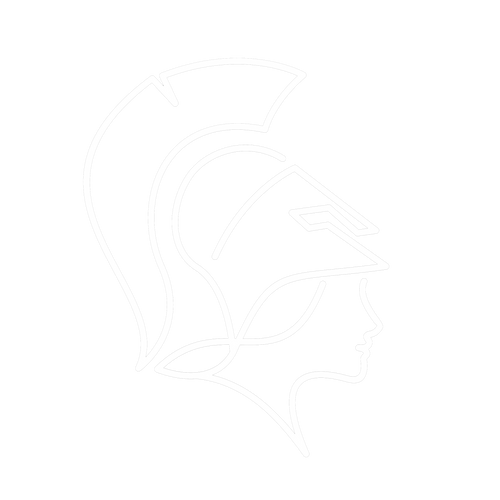

‘Women Welders at Work on Pieces of Metal – In the Centre a Beginner Receiving Instruction’, E. C. Woodward’s workshops at 5 and 7 Johnson Street, Notting Hill Gate, Sphere, 11 March 1916 (Thomas, 2020)

Écriture féminine

She is beautiful and she is laughing

Arts and Crafts was in its infancy in the mid-to-late 1800s. Men looked without seeing, avoiding the gaze of women in their milieu.

"Hold still we’re going to do your portrait, so you can begin looking like it right away."

In context of Pre-Raphaelite women, Hélène Cixous’s words here could hardly be more fitting: compare Elizabeth Siddal's self-portrait with Siddal sitting for Dante Rossetti...

Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Beata Beatrix (c.1864–1870)

The Pre-Raphaelites wanted Siddal to look like her portrait. She was gold to be cast in their design.

The sensual, desirous muse portrayed by the brotherhood has nothing to do with Siddal's own work in which, with heavy-lidded eyes and lips pursed, indifferently, she looks right through you.

Siddal wrote herself. In poetry and in painting she resisted “becoming her portrait” as best she could. In her lonely, often hopeless poems, Siddal embodies Cixous's double-bind: Elizabeth Siddal is caught between “abyss” and “medusa”: simultaneously trying to be seen, to be loved, while also longing for the next life - an end to her suffering.

Just like the mythological Perseus, the Pre-Raphaelites looked indirectly at Elizabeth. Grimly they walk backwards towards her before symbolically 'cutting off her head' (they drove her to a fatal overdose).

But Cixous defends, vindicates, Medusa…

"You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing"

To Cixous, Medusa’s petrifying gaze symbolises man’s fear of woman’s voice. Only with back turned and eyes averted so as to avoid her fatal curse does he confront her...

So what does Medusa really symbolise? Is she truly that timeless and petrifying monster? Or instead, might we perhaps see her monstrousness only as man's writing of woman; a kind of subjective horror, projected by the male gaze, at the insistence of women to be heard and to carve out her own space. In line with Cixous, then, and for contextualising what follows, we reinterpret Medusa as a symbol of women’s resistance against those who tried to refuse her entry into the Arts and Crafts movement in the decades following Siddal’s tragic passing.

And of course, Arts and Crafts was only a beginning: the groundwork of a revolution for women artists and artisans.

Head of Medusa; Red jasper mounted in gold with white enamel, Benedetto Pistrucci (Cameo, 1840–50) and Carlo Giuliano (mount, ca. 1860) MET

Her inevitable struggle

The simplest ornament - made even of the less precious metals,

and set with the cheapest of stones -

may be

lovely and satisfying

The Guild system was central to the Arts and Crafts. The medieval aesthetic so favoured by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was repeated by artisans - professional crafts-workers learning and labouring together - sharing ideas and partnering equally in ventures.

The objectives of the Guilds were summarised as follows:

1. To make beautiful things for the homes of simple and gentle folk

2. To revive the desire for beauty in the things of everyday use

3. To inspire art workers to excel by placing the work of various designers and craftsmen side by side

William Morris and Charles R. Ashbee were members of the Art Workers’ Guild established in 1885. Ashbee in 1888 set up his own Guild and School for Handicrafts. The Guilds also reflected ideals of William Morris: to resist mechanisation and industrialisation of the arts while defending fair labour and a fair wage, and so on.

Ashbee’s guild was, at first, widely celebrated.

Charles R. Ashbee: Pendant Brooch, Silver and gold with blister pearl, garnet and brilliant-cut diamond, ca. 1900; V&A

Arts and Crafts at Lost Owl: Silver and vitreous enamel locket by Henry William King with printed image of May Morris's "Orange Tree" embroidery

However, in a jewellery review from 1907 - ten years after the founding of Ashbee's Guild, one author writes…

When I undertook to write this paper, I asked Mr. Ashbee about certain jewellery which I had recently seen in his Brook-street shop. He replied that … a good deal of the jewellery was not up to the standard of the earlier work, and the bulk of it was not designed by him. (Hadaway, 1908)

Women were not permitted entry to the guilds. So just as Ashbee’s project was running into difficulties, in the first decade of the 1900s, several women got together to launch their own project and in 1907 the Woman’s Guild of Arts was established. These women were already well-established working professionals in their own right.

- E.C. Woodard had won an award in St. Louis for her metalwork and had been running her own shop since 1884.

- May Morris - daughter of the aforementioned Morris and of Kate Burden - had taken on the family business and had given lectures in Birmingham 1899-1902 where...

- Constance Smedley, was attentively listening, and where...

- Georgie and Arthur Gaskin were just beginning work at the time.

Works by Arthur & Georgie Gaskin

Arthur & Georgie Gaskin: Silver set with green stones and blister pearls, with wire-work and filigree decoration, Birmingham c. 1909 (V&A)

Constance Smedley officially opened the Lyceum Club in 1904 having been “thrilled at lectures from May Morris”. Gertrude Atherton, a journalist and woman’s rights activist visited the club in 1908, wrote of its “unique atmosphere” of which “no other woman’s club on earth can boast”, calling it ‘The Greatest Woman’s Club in the World’. (Thomas, 2020)

The Lyceum Club would soon go global…

Arts and Crafts exhibition of the Lyceum Club at the Modern Living Spaces Gallery, Wertheim department store, Berlin 1905 (Thomas, 2020)

At this stage it's interesting to note a comparison: while women across England were banding together and following faithfully the principals of the guilds, what of that most prestigious men’s "Art Workers’ Guild"? It had become a “bohemian gentleman’s club, smokey and exclusive” wrote Art Historian Alan Crawford, where “a narrow and tiresome aristocracy” was to be found “working with great skill for the very rich”. (Thomas, 2020)

Moreover, “working women showed no interest” according to Gere and Munn.

The gender exclusive socialism of William Morris’s movement - it appears - was eating itself.

Another challenge these guilds and the movement faced was the success of Liberty & Co. of Regent Street...

C.R. Ashbee is known to have felt indignant at the extent to which Liberty's borrowed Guild of Handicraft ideas, adding insult to injury by undercutting the prices which the Guild had to charge.

(Gere and Munn, 1996)

Jessie M. King: designs for Liberty & Co.

Liberty's was precisely what the guilds had been resisting: factory production en masse that sidelined the craftsperson, their design and their expertise. Gere and Munn note how the mechanised process resulted in clumsy products unfit for their purpose:

"enamelling is used where it is certain to get knocked, and cabochon-cut turquoise matrix is lightly cemented on to hollow-ware pieces that are going to have to be washed!"

A Mrs Hadaway captures the confrontation between the machine-made and the hand-made in an article of 1908:

"the jewellery of commerce cannot possibly be considered as works of art - no matter how elaborate and expensive...

It is only when Nature is translated by the artist that it becomes Art, not when it is slavishly copied. One would have supposed that this was so well known that there would be no need to say it; but apparently not.

It is only the individuality of the artist that makes the Art worth anything, and if twenty artists were to make a literal copy of, say, a lizard, and if all made it exactly like the model, it would be more a mechanical accomplishment than a work of Art."

She goes on to entertainingly describe her experience at the gallery of the Fine Art Society thus:

"...it came upon one

as a shock- an orgy of delicate realism."

(Hadaway, 1908)

And no doubt the same Mrs Hadaway would have adored the work of Florence Koehler, an American woman working in London at the time under the tutelage of a member of the guild. Koehler had left her husband to travel Europe with a female companion in the early 1900s. In London she made bespoke pieces for an artistic milieu who appear to have greatly admired her.

Florence Koehler: Ring and Pin c.1905 (MET)

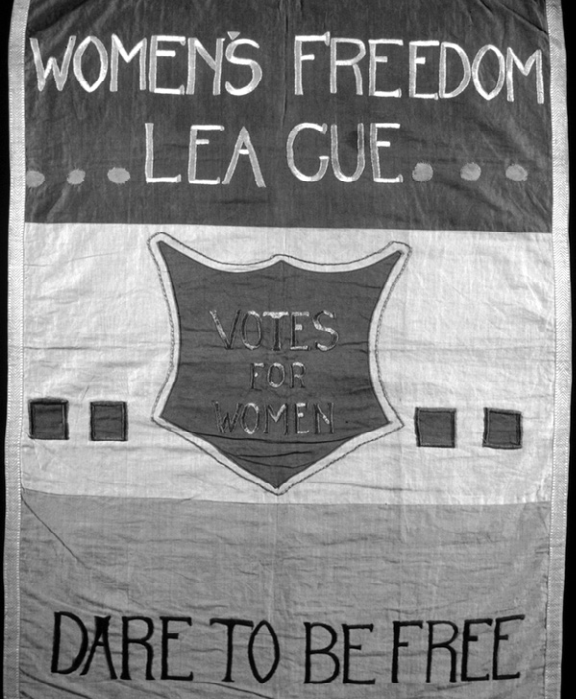

Meanwhile, within women artists' movement and their guilds, Suffragism was on the march. Florence Koehler seems to have been politically aseptic, an ascetic dedicated entirely to her craft. But others were more closely involved with Votes for Women.

Although the Gaskins have no "documented links" with the suffragette movement, authors cite Arthur Gaskin's socialism and the couples frequent combination of the suffragette colour scheme - white, purple and green - as potential indictors of their sympathies. Writing in "The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society", Elizabeth S Goring says of the Gaskins that "they or one of their clients must surely have had such links".

‘Dare to be Free’ designed by Mary Sargant Florence, c.1908–1914 (Thomas, 2020)

While May Morris provided materials for the banners at women’s marches, her support of Women's Suffrage often seemed tentative. On her tour of the United States in 1897, an audience famously - for an hour - bombarded her with questions on women’s liberation whereupon she “shrank into herself as a snail into its shell”, according to the Washington post.

But one should not be overly critical of Morris in this regard, in my view. Morris, perhaps, simply knew what her role was within the movement: she moved behind the scenes; she provided spaces and materials; she spoke to suffragette audiences in the UK and the US, creating and furthering women’s spaces while pushing for better working conditions and recognition of women’s work.

That was her role. Consider her words while in the States:

"People crowd to hear me… but they are disappointed that I do not speak of personal matters. And you can imagine how puzzled the reporters are: the daughter of a great man missing her opportunity and not talking about him."

"My interest in suffrage is linked with the guild workers in the arts and crafts."

With an ironic flourish, she casts off the "phallic" symbol and redirects the discussion to awareness-raising and women's struggles.

May Morris's fight was not on the street, but with women "on the shop floor": for the recognition of the newly established women's spaces and the women within them as hardworking professional equals at a time when other spaces remained closed to them.

Arts and Crafts at Lost Owl: Necklace, by Arthur & Georgie Gaskin - leaf and flower motifs and chrysoprase in sterling silver c.1905 (see in store)

She is everywhere (even in Deerfield)

"Just at evening we drove over to Deerfield... through the most luxuriant and beautiful country

that we had seen anywhere on our journey.

Even now, in the latter part of October, the grass is most vividly green,

thickly matted and rich as the shag of velvet..."

Benjamin Silliman

In Deerfield Massachusetts in the late 1800s, leafy oak and maple branches embrace above the well-kept, perfectly flat and unmistakably North American lawns of large, gabled wooden homes lining a main road, a third of which are owned by women.

After the American Civil War, women were in the majority in the U.S. They inherited property and set up businesses; they bought and renovated houses and converted front rooms into studios and parlours where they sold the products of their labour.

At the first American Arts and Crafts Exhibition 1897, held 129 miles east of Deerfield in Boston, half of the 160 craft-workers exhibited were women.

Here, the astonishing work of Marie Zimmerman was first shown. She was originally from New York State and frequented the city's museums. She worked between 10-12 hours a day and learned everything - almost literally everything. “From tiaras to tombstones”, she said. Masonry, metalwork, furniture, design, enamel…

Rings by Zimmermann: Gold, enamel, and zircon; Gold, enamel, and intaglio carnelian

“I have tried to bring back the old idea of the artist that flourished in the days of such men as Michaelangelo and Cellini. They were masters of a dozen crafts and they used all of them in producing perhaps one object”

In Zimmerman's work, it's difficult not to recall both Castellani, in its archaeological themes, and Cartier's tutti-frutti, and even Art Deco aesthetic. And yet the naturalism, the slight irregularities, the tasteful asymmetries and often striking choice of materials clearly denote a language deeply rooted in the Arts and Crafts.

Works by Marie Zimemrman

In Massachusetts and New York the game was afoot, but Chicago was where women were really getting their feet in the door.

Florence Koehler made a stop here before travelling to Europe and to London, as did Zimmerman.

And when May Morris toured the States in 1907 she too stopped in Chicago to give a lecture at Hull House. Established a decade earlier, in October 1897, Hull House was the birthplace and headquarters of The Arts and Crafts Society of Chicago.

The House had an open doors policy. It provided work and learning opportunities for women of all backgrounds, and lectures were given on politics, philosophy and the arts: a women’s forum; a women-centred ancient Athens. It was here, at Hull House that May Morris received that intense questioning on her views of the women’s liberation movement in England.

Another two American women of the time that everybody should know are Jane Addams and Ida B. Wells...

Addams - founding member of both Hull House and the Arts and Crafts Society of Chicago - was a white, upper-middle class lady of means. She advocated for Frances D. Roosevelt, for the trade union movement, and became an international anti-war activist. But she also had some uncomfortable views regarding race, crime, and eugenics. When Ida B. Wells - black rights activist and journalist born into slavery - confronted Addams on her statements about race, Addams not only listened to Wells, but continued inviting her to talk, amplifying Wells’s fight against the Chicago newspapers which were promoting segregation in schools. A battle which the two women, in collaboration, finally won. The newspaper articles stopped.

Reminiscent of Marie Zimmerman at Lost Owl: carved jade panels each depicting a pair of flowers in 18 carat gold (see in store)

In one another we will never be lacking

“Publishing houses are the crafty, obsequious relayers of imperatives

handed down by an economy that works against us and off our backs”

William Morris and Charles Ashbee owned the publishing house - Kelmscott Press. William Morris established it during his lifetime after which it was purchased by Ashbee.

Cixous, several decades later, would call for a “space that can serve as a springboard for subversive thought, the precursory movement of a transformation of social and cultural structures.”

It seems that the women of the Arts and Crafts movement had already been thinking along the same lines. They pulled the discourse - political, aesthetic, creative - out of the echo chambers of bohemian men into the streets and into both public and women-only spaces. The discourse became not only woman-to-man, but perhaps more importantly, woman-to-woman. Criticisms and counter-movements came too from women. One might go so far as to say that a grammar, first laid down by the Arts and Crafts in the hands of women artists, gave rise to a growing and ever-more colourful language.

Margaret De Patta (1903-1964) at work

In the decades to come, the World Wars and austerity would have crippling effects on innovation in the crafts.

Geoffrey Munn writes:

patrons were less willing to spend money on craftsmanship and design; instead, those who wanted contemporary jewellery were more inclined to buy a show of precious stones for investment rather than for fashion; and least of all, for art.

And the great postwar brutalist, John Donald, wrote about his early days (probably around 1950s):

in the early days we could not afford gold, so we made them in silver and gilded the final piece

Nevertheless, an international discourse with women at the helm had risen out of the ashes and internal contradictions of whimsical, medieval and bohemian men’s socialist clubs. And although, in the early-mid 20th Century, large-scale jewellers (Cartier, Liberty, Tiffany's etc.) dominated a market in which metals and precious stones were all but inaccessible to small studios, you cannot kill an idea.

Remember Mrs Hadaway's article from 1908:

the simplest ornament- made even of the less precious metals, and set with the cheapest of stones- may be lovely and satisfying

Our new love for the innovative works of the multi-faceted studio designer-jeweller, with her focus on the intersection of ancient principals of craftwork and technique and more lofty and evolving ideals of contemporary art, was far from lost.

Around the world this intersection had been redefined by women who, I would argue, through international solidarity, dedication, and inclusiveness, succeeded in making the Arts and Crafts into the movement we recognise today.

As we shall see in the next publication - Postwar Modernism and Talismanic Numinousness - new generations of women working at this intersection (Margaret de Patta, Gerda Flockinger, Wendy Ramshaw) would shepherd the fundamental principles of Arts and Crafts, transformed by new philosophies, through the 20th Century in the Bauhaus, Surrealism, Constructivism, up to and beyond the postwar Brutalism of the 1960s and 70s.

So when you hear "Arts and Crafts", when you see it and when you wear it, don't just think Wi***** Mo****. Don't think of those closed, dried up ideologues that so quickly skewered themselves on their own prejudices. Think bigger. Think beyond. Think of solidarity, liberation, of today's unheard voices, unheard-of songs, and ongoing struggles for equality.

Arts and Crafts as Lost Owl: Necklace with leaf and flower motifs in moonstone and silver c.1900 (see in store)

Sonia Delaunay: 18-carat gold and enamel "Flamenco" pendant

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Helene Cixous, The Laugh of The Medusa: https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/nietzsche1313/files/2017/04/The-Laugh-of-the-Medusa.pdf (1976)

Zoë Thomas, Women art workers and the Arts and Crafts Movement, Manchester University Press (2020)

Charlotte Gere and Geoffrey Munn, Pre-Raphaelite to Arts and Crafts Jewellery (1996)

INTRODUCTION

Slavoj Zizek on "symbolic castration" (youtube)

ECRITURE FEMININE

Helene Cixous, The Laugh of The Medusa

Mrs. Hadaway, Developments in the Art of Jewellery, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Vol. 56, No. 2881 (February 7, 1908), pp. 287-297

May Morris in the US: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1748&context=tsaconf

SHE IS EVERYWHERE

Marla R. Miller and Anne Digan Lanning,'Common parlors' : women and the recreation of community identity in Deerfield, Massachusetts, 1870-1920 /

Marie Zimmerman; newspaper cutting: https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/57480446

Marie Zimemrman; article: https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/the-unknown-jewelry-of-marie-zimmerman/

In one another we will never be lacking

Geoffrey Munn , Forward: https://geoffreymunn.art/grima-foreword

Johndonald.com, Gallery: http://www.johndonald.com/gallery.html