Post- War Modernism and

Talismanic Numinousness:

From the Arts and Crafts and Back Again

Heaven, Hell, and The International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery

“That’s a rhizome!” I thought, looking for the first time at British post-war modernist jewellery.

A rhizome is a root system - network, nodes - extending laterally underground. It’s also a poignant philosophical concept introduced in the 1970s.

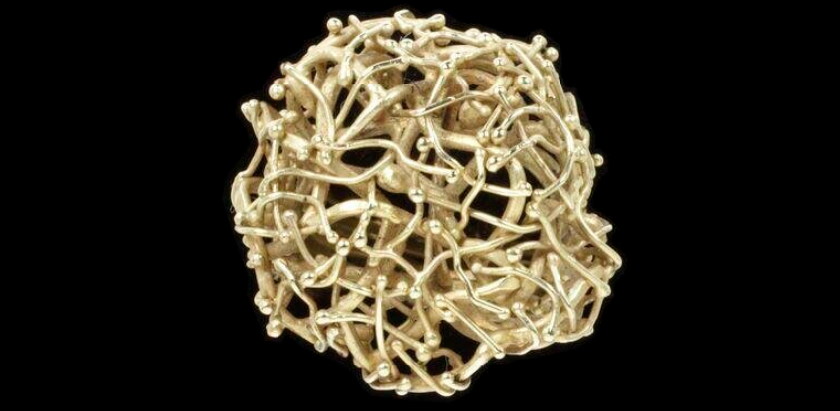

E.R. Nele: Gold ring (1957-60) V&A

But more on rhizomes later...

Cut to London (1961, October-December): Goldsmiths' Hall is holding the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery. Andrew Grima, John Donald, Gerda Flöckinger, just a few - still upcoming, largely under the radar - on display alongside Fouquet, Cartier, Picasso, Dali, in a celebration of Modernist Art promoted by De Beers, The V&A Museum, and the Goldsmith Company.

After two world wars, Modernism is reborn again. It’s another chance.

This landmark 1961 exhibition hopes to...

encourage cooperation and mutual confidence between all aspects of the trade and the artist-craftsmen'

...and…

revitalise what was seen as the stagnant, value-orientated state of jewellery design at the close of the 1950s

E.R. Nele: Gold wire collar, displayed (with the ring above) at the 1961 exhibition V&A

It is, as they say, always darkest before dawn and in the early 1960s a small band of artist craftsmen were determined to revive and maintain the high standards of the past

In 1961 that “small band” (the British modernists at the Goldsmith Exhibition) weren't so 'splendorous' yet. Nevertheless, from their small studios - several in London's Art Schools - an incipient proto- Brutalism was indeed taking shape...

- the organic forms and textures that Constructivism had dispensed with were restored,

- and sometimes combined with weaving contours and rough unfinished edges favoured in Surrealism.

- Geometry and repetition was not exact and mathematical, but now flowing, as though improvised.

1961 was a “nod to Renaissance metalsmithing and the cross-pollination of the plastic arts… a 'multidisciplinary practice,' was key to the approach of this exhibition”

Also shown at the 1961 exhibition...

- J C Champagnat - Silver-gilt ring (V&A)

- F.E. McWilliam - gilded silver bracelet (V&A)

But... Renaissance... metal-smithing... multidisciplinary... wait...

Arts and Crafts … again? We're returning, again, to the premodern - Pre-raphaelite-like - searching for a lost and naive garden-of-eden naturalistic beauty from which we tragically went astray?

This 1961 exhibition was energising, and drawing attention to, a new generation of studio (anti-mass-produced or maison) jeweller-artist-artisans who would soon Make Jewellery Dazzling Again.

Geoffrey Munn, in the same forward, quotes Aldous Huxley’s Heaven and Hell…

Of all the vision-inducing arts, that which depends most completely on its raw materials is, of course, the art of the goldsmith and jeweller.… And when to this natural magic of glinting metal and self-luminous stone is added the other magic of noble forms and colours artfully blended, we find ourselves in the presence of a genuine talisman.

Another extract from Huxley’s Heaven and Hell…

“...a flame is a living gem, endowed with all the transporting power that belongs to the precious stone and, to a lesser degree, to polished metal. This transporting power of flame increases in proportion to the depth and extent of the surrounding darkness. The most impressively numinous* temples are caverns of twilight, in which a few tapers give life to the transporting, otherworldly treasures on the altar.

*Numinous is something denoting the presence of the divine/sublime.

Lost Owl: citrine, two-tone 18 carat gold ring (c.1970s) (see in store)

...very reminiscent of E.R: Nele's "melting loops"... (title photo)

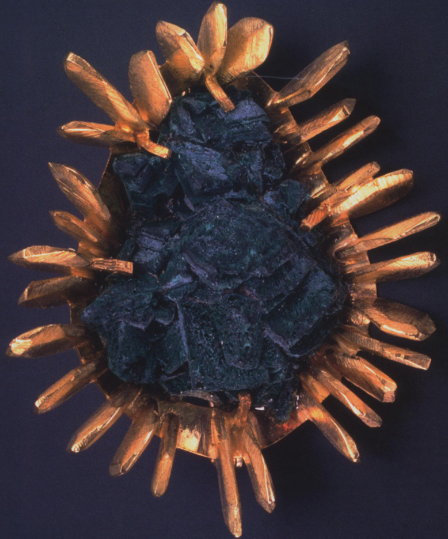

Munn praises the “dazzling” jewellery of Andrew Grima who seemingly “waved an alchemist’s wand over very modest materials like ginkgo leaves, lichen and even fragile pencil shavings and transmuted them into gold”, noting the “rich yellow gold … his perfect colour pitch”.

And there is something “alchemic” in the transformation of earthiness, textures of bark or roots into shimmering and wearable organic "talismans"...

Andrew Grima "pencil shavings" brooch (1968)

Lost Owl: bottle-green tourmaline, 9ct gold ring, textured twigs and branches (1960s) (see in store)

Approaching the 1960s and 70s, and works by Wendy Ramshaw, John Donald, Andrew Grima and other British Post-War Modernists - their talismanic numinousness - we will look awry at them, in the refracted light of others from the first waves of modernism and the avant-garde in the early 20th Century.

There had also been a revolution in form since the Arts and Crafts, brought about by the avant-garde.

“Figurative representation was out” Barbara Cartlidge said. Zizek put it like this:

From the very beginning, radical avant-garde distrusts beauty - beauty becomes ideological, a conformist idea… The work of art should not reflect reality… but somehow render the truth of our predicament, (by) avoiding beauty.

From contorted metals scattered among reflective shards, and turbulent mounds of exploded brickwork in Europe and Russia’s war torn cities, it seemed - already in 1920 - that a New World might be born…

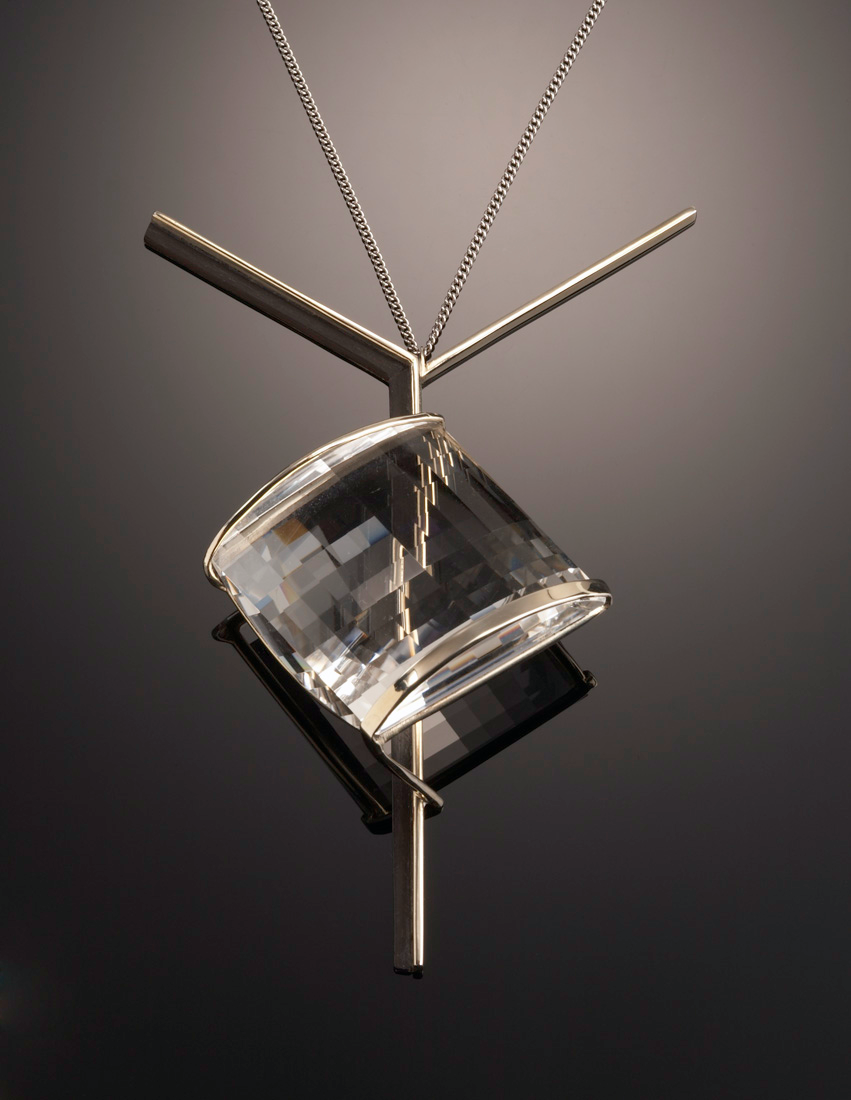

John Donald: Brooch-pendant (1963) The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

HEAVEN and rigorous spiritual discipline

Catch your stones in the air.

Make them float.

Paris, 1914, the eve of World War I: seventy-six Russian painters displayed works in Paris, France, at the Salon des indépendants.

For the Russians, austere and angled geometric constructions was the art of urban space, industrialisation and modernisation.

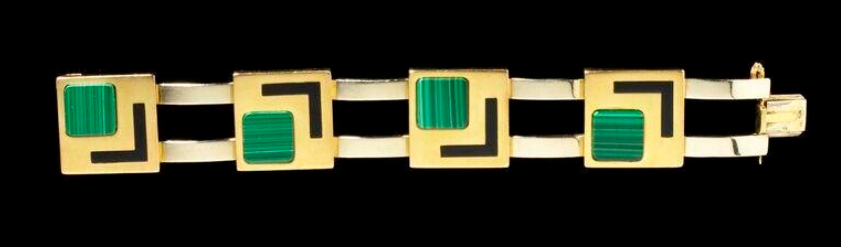

Jean Fouquet: Bracelet, gold with malachite and black lacquer (Paris c.1929) V&A

Supposedly, engraved on the entrance to Plato’s academy in Ancient Athens were the words:

Let no one ignorant of geometry enter

Lost Owl: Onyx and Diamond, 18ct white gold ring, mid century (see in store)

Our creations are more real than nature, insisted Plato. What we experience as “the natural world out there” is only a world that emerges, poorly imitating the perfect geometric realm of pure human idea.

And the world out there - torn apart by the Great War - was looking to put itself back together again.

Artists searched for a new language for this new chapter - a language freed from imitating the imitation; a language to express something more fundamental and profound.

Jean Fouquet, in the 1920s, was collaborating with the great modern architect and thinker Le Corbusier in the artistic Parisian publication L’Esprit Nouveau in which Corbusier dramatically pronounced...

A grand epoch has just begun. There exists a new spirit.

There already exists a crowd of works in the new spirit

to be met with especially in industrial production.

...bracelets, brooches, and pendants are geometric constructions free of any reference to nature, made of yellow and/or white gold, precious or semiprecious stones or both, and sometimes enamel. Voids are often juxtaposed with the geometric shapes... (Greenbaum)

Jean Fouquet: gold and onyx bracelet

Moholy-Nagy was a "Utopian Idealist", illustrated by his own words cited by Greenbaum...

"The arts are necessary for everyone’s physical and psychological well being.

Art expresses the spirit of the times

The art of our century, its mirror and its voice, is constructivism…

primordial, without class and without ancestor. It expresses the pure form of nature, the direct color, the spatial element not distorted by utilitarian motifs.

In constructivism the process and the goal are one and the same - the spiritual conquest of a century of technology.”

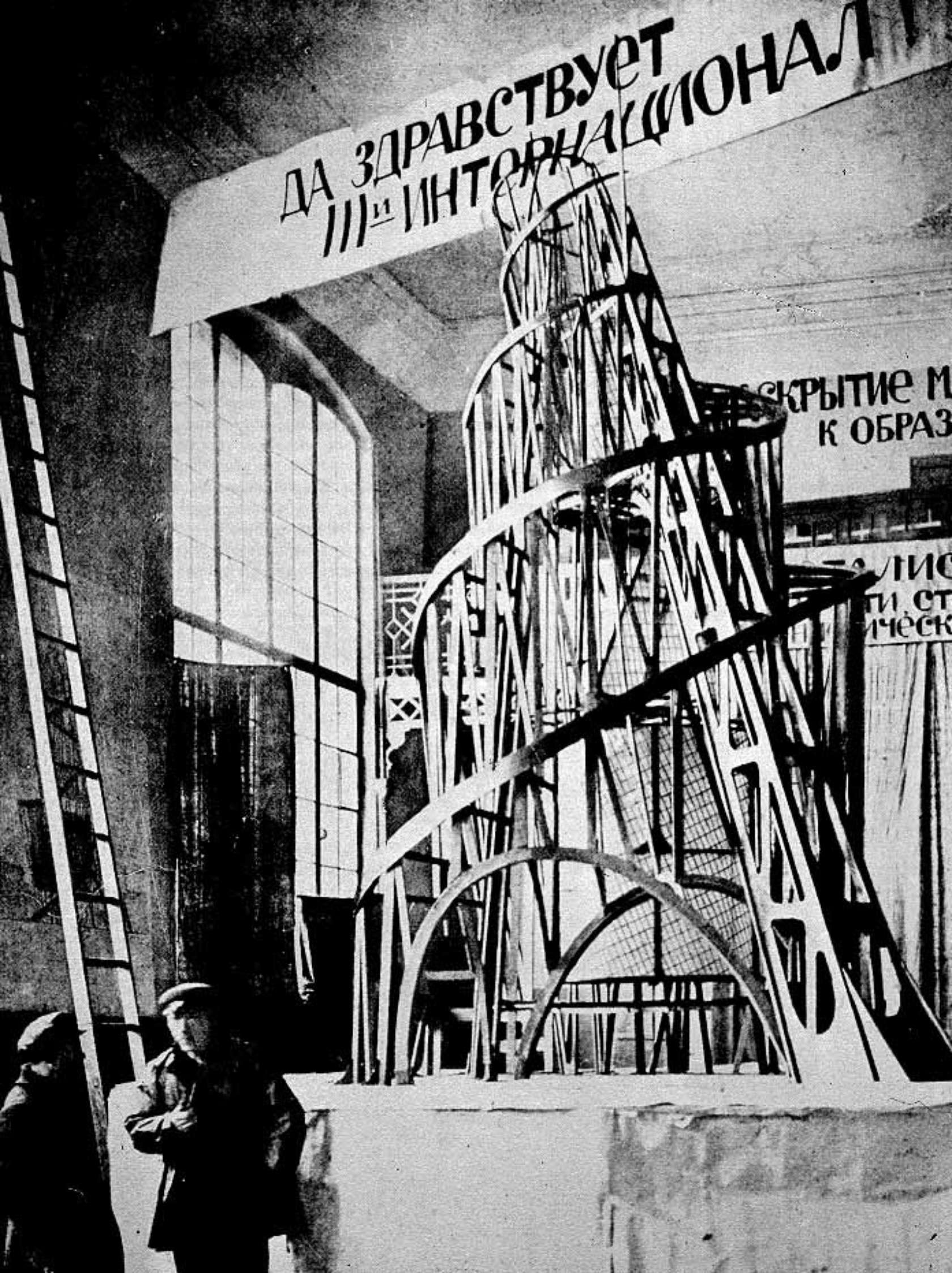

Tatlin's monument to The Third International

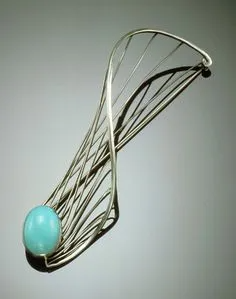

Irena Byrnner, Earrings

Of course, when the Nazis came to power in 1933, a jewish communist immigrant in Berlin had little option but to flee, and so Moholy-Nagy was on the move again. From London, he was invited by Chicago's Association of Art and Industry, to start a new design school, which opened in 1937, and was named The New Bauhaus...

“Catch your stones in the air”

he told her.

“Make them float”

Toni Greenbaum describes how de Patta strived to achieve this aim using “asymmetrical design, cantilevered parts, and hidden or invisible supports”.

Moholy believed that jewellery as art could transform his vision of architecture, structure, and form - “the interplay of space, light, and motion” - into sculptures that might be worn.

Lost Owl: baguette cut diamonds (3.75 carats), 18ct white gold ring (see in store)

HELL and indulgent, permissive spontaneity

Christmas, kidneys, teardrops dropping,

pendant, dancers …

There is clearly something constructivist about this perfect Platonic realm, or Huxley's “Heaven” - his numinous temples, caverns of twilight, and transporting power of the living gem: the flame.

Heaven is light and form, luminosity and zen-like eternalism: free from desire, from the confines of utilitarian productivity.

So what if surrealism is Huxleyan Hell?

Cut to Winter in Greenwich Village, New York, sometime in the 1940s:

Bohemian silversmith and eccentric artist weirdo Sam Kramer holds a Christmas soiree.

Kramer describes it:

pierced by shrill cries of maddened customers and made hideous by the steady groaning of the shelves, under their holiday burden of germs and worms and amoebas and fetuses and kidneys.

Yes, and fragments of whitish coral, like decayed bone, clutched by silver . . . startled eyes with teardrops dropping . . . schizophrenic dancers, pendant . . . and nightmare creatures in brutal variety.

And with it, Nature too returns in Surrealism: not geometry, not symmetry, but the organic motif only contorted, made indecipherable - knowledge is not beyond nature, but within nature, and yet inaccessible.

In “Doors of Perception”, Huxley uses schizophrenia to describe the 'bad trip' - “the infernal road”. Schizophrenia is for him “the inability to take refuge from inner and outer reality”.

“a strictly human world of useful notions, shared symbols… scares (the schizophrenic) into interpreting its unremitting strangeness, its burning intensity of significance, as the manifestations of human or even cosmic malevolence”

It’s like plunging into earth, engulfed by things all too human without being able to make sense of them - human experience and history flies off the autopsy table...

Selected works by ART SMITH, Sam Kramer's neighbour in Greenwich Village

And Huxley refers to The Tibetan Book of the Dead…

the departed soul ... shrinking in agony from the Pure Light of the Void, and even from the lesser, tempered Lights, in order to rush headlong into the comforting darkness of selfhood as a reborn human being, or even as a beast, an unhappy ghost, a denizen of hell.

Heaven is light and form, and Hell is the persistence of senselessly functioning things…

...Christmas, kidneys, teardrops dropping, pendant, dancers...

Lost Owl: solid silver, applied wave motifs, amethyst cabochon set in gold (1960s) (see in store)

Modernism, Take 3

ACTION! London, 1952, the Central School of Arts and Crafts:

Austrian-born, Gerda Flöckinger, 25, begins a two year course at the prestigious school founded in the wake of William Morris and John Ruskin in the heyday of the original Arts and Crafts scene.She attends classes with a graduate of the school, British painter, Mary Kessel. Kessel in the years prior had been an 'Official War Artist' documenting in sketches, paintings, and charcoal drawings Germany’s ruined cities, displaced persons camps - women and children living in the terrible aftermath - and the only recently discovered concentration camps…

Refugees: '... pray ye that your fight be not in the winter...' Matthew XXIV, 20 (Kessel, 1945)

Flöckinger, on her experience studying under Kessel and other British painters said...

Without this class I don't know whether my own ideas would have developed in a similar way.

No doubt in part inspired by Kessel’s work, texture is key in Flöckinger’s innovation,

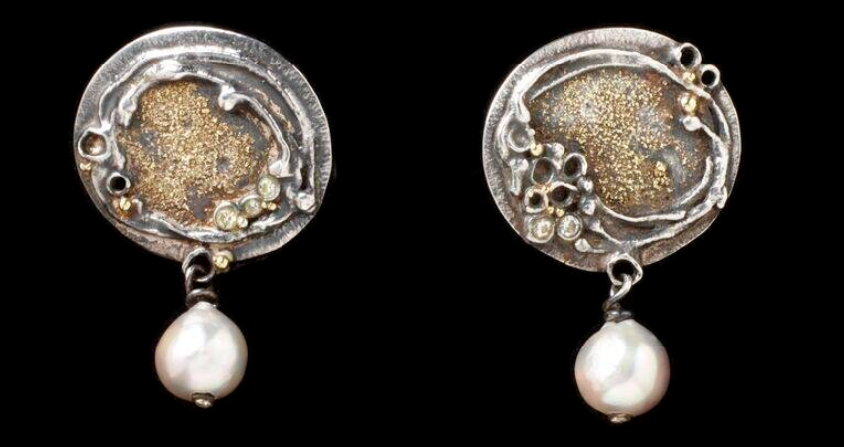

Gerda Flöckinger: earrings of oxidised silver, gold, pearls and diamonds, (1975) V&A

Gerda Flöckinger: Bracelet of silver and grey pearls (London, 1973) V&A

Melting and fusing gold and silver to create liquid, swirling movements, oxidising surfaces - darkening through chemical processes - for contrast and emphasis of motion in the metal but also for a worn, even baroque finish…

Gerda Flöckinger had left Austria before the outbreak of war, in 1937. She had travelled through Italy, and been inspired to study jewellery-making by designs she saw the Venice Biennale. Throughout the 50’s, she gradually gained significance, finally selling her pieces to Goldsmiths' Hall (1958) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (1960), two of the key actors in the organisation of that great exhibition of Modernism, the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1961, where she was invited to display her work.

In 1971, Flöckinger was on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum at its first solo exhibition of work by a living jeweller.

“Sinewy linear movements … like tendrils from an exotic climbing plant…”

...reflected one observer.

Lost Owl: Attributed to George Weil, 18 carat gold, emerald and diamond set in platinum (1960s) (see in store)

A mere 25 minutes walk from the Central Arts and Crafts School (now Central Art and Design) - at which Flockinger had taken her transformative classes with the British painters - southeast towards the Thames and St Paul’s, is Goldsmith’s Hall, itself just behind Cheapside: the historic London market street - once "the busiest thoroughfare in the world" according to Charles DIckens - where centuries earlier armourers and silver and goldsmiths had forged and sold their wares.

Cheapside, London

Before the Great Fire of London, a collector stashed hundreds of pieces from all over the world on Cheapside and it was unearthed by workers in 1912.

And, in the late 1960s, John Donald brought metalwork back to the historic street, setting up a retail outlet and workshop.

When I started in the mid-to-late 1950s, there were very few new things being made in jewellery…Innovation just hadn’t happened for 20 years

I looked at all the products of the bullion dealers and then itemised them.

From these various forms I cut square rods, oval tubes at angles and into small pieces

At that great exhibition of 1961, as has already been observed, Brutalism's sinewy statement extravagance and complex network constructions had not yet fully matured. It has been difficult to confirm the exact works (only four) displayed by John Donald at this event, but I believe they were the following...

"In the early days we could not afford gold, so we made them in silver and gilded the final piece"

"In the early days we could not afford gold, so we made them in silver and gilded the final piece"John Donald's most important contribution - perhaps - in terms of aesthetic and 'the shape of Brutalism to come', was sis 1960 gold and malachite Brooch...

Lost Owl: . sterling silver pendant, white quartz druzy (London 1965) (see in store)

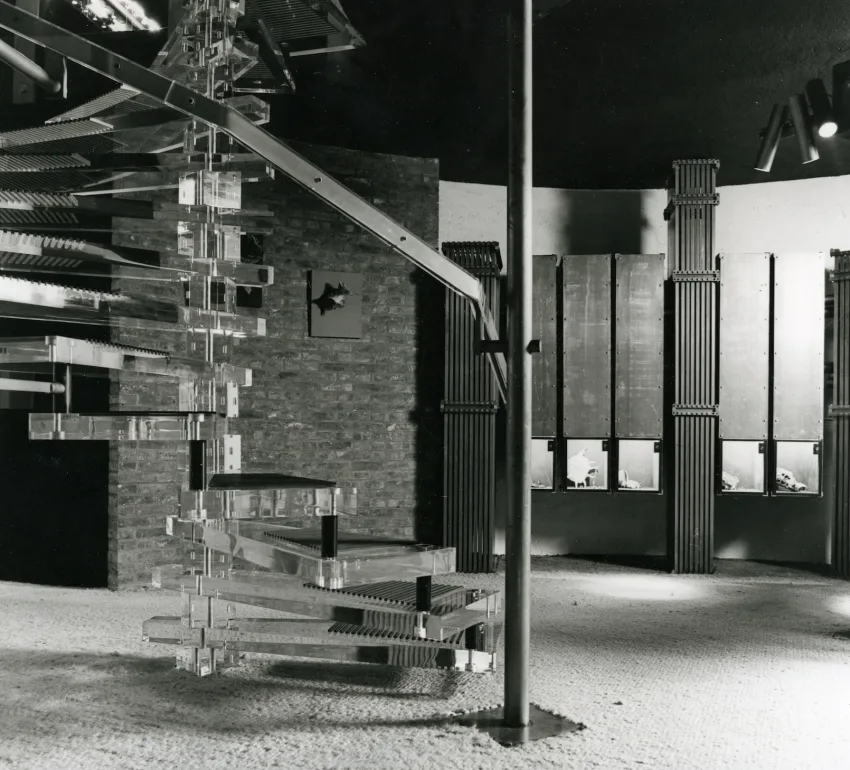

Follow the Thames back west towards Buckingham Palace and Picadilly, and Andrew Grima’s Jermyn Street Boutique could be found. The outlet itself was a tribute to Grima’s eccentricity. His two architect brothers designed it.

A massive automatic cast aluminium door-sculpture by the artist Geoffrey Clark outside...

...a spiral staircase by engineer Ove Arup inside and a frieze by another sculptor, Bryan Kneale, along the wall. ..

With Grima’s work after 1961- glamorous, bright and bold, intricately constructed yet organic, living, raw and moving - we see Brutalist jewellery (its talismanic numinousness?) fully forming, becoming rhizome...

WORKSHOP SCENE: Five or six bespectacled men in white overalls scuttle between cluttered workbenches; moss and branch, pencil, brooch, hammer, paint and diamonds, a big machine screeches...

Plaster is poured over twigs, bark, lichen, wood shavings enclosed in metal cylinders, which are then fired in a kiln. After firing, only the imprint of the organic material remains inside the plaster and molten gold is poured inside. The plaster-cylinder is placed in a machine which spins it at dizzying velocity to fill out every detail of the mold left by the burned-away organic matter. A perfectly textured golden twig, bark, lichen, or wood shaving emerges now to be shaped, built upon, by Grima and his team.

Andrew Grima: brooch, textured gold, set with round brilliant-cut diamonds; c. 1966 18k yellow gold

Andrew Grima Brooches (Clockwise from top left)

- Yellow gold textured wire with ruby and diamonds (1966).

- Polished yellow gold wire with marquise emeralds and diamonds (1964)

- Pine twigs brooch: yellow gold with carved cabochon sapphires and diamonds (1962) (citation)

Rigorous Discipline WITH Indulgent Permisiveness

Wendy Ramshaw was younger. Too young to get the leg-up that the 1961 exhibition offered the others. Jeweller, ceramicist, sculptor, Ramshaw became best known for her “fluid” approach to design.

Her sets of rings, or “pillar rings” were essentially a three-in-one art piece:

- A complimentary set created by the artist (the author)

- A sculpture displayed upon its bespoke mount (the piece)

- Independent pieces to be combined, recombined and worn as the wearer desires (the wearer)

“Most of my jewellery is made in parts or sections, so that the owner can share in the way the piece is worn.”

Wendy Ramshaw: three enamelled and gem-set gold rings mounted on an acrylic stand, (1971) V&A

it is language which speaks, not the author (Barthes)

The role of the reader-interpreter - the wearer, in the case of jewellery - becomes key: the piece is fully realised only through its expression in his, her, their hands.

(the text is) a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture (Barthes)

Eight ring set: cabochon blue chalcedony, moonstone, or sapphire; 18k yellow gold and sterling silver

Wendy Ramshaw, 7-ring set

Neo-Constructivism (or architectonic), perhaps... perfect geometry, but "randomly" scattered diamonds - one pearl among the diamonds - a Brutalist improvisational or free-form touch...

And when to this natural magic of glinting metal and self-luminous stone is added the other magic of noble forms and colours artfully blended, we find ourselves in the presence of a genuine talisman.

Recall the rhizome: as opposed to a tree - a vertical structure, necessarily connected in a hierarchical system (you cannot invert or recombine root, trunk, branch, leaves) - the rhizome has no centre, no direction, from any node a root may spring, reaching out toward any other.

For french philospher Gilles Deleuze, this opposition was socio-political. It had very human ramifications. In the context of the 1960s sexual revolution, the body was the site of a revolution: hetero-patriarchal norms were being challenged - the New Age revolution, hippy counterculture, free love - these notions were reimagining society as a non-hierarchical rhizomatic structure.

Just as Ramshaw’s fluid jewellery-sculptures, the human too becomes fluid - not fixed, figurative or cast in the image of rigid societal demands, but an artwork in itself connecting and reconnecting with a thousand others, always recreating itself.

The body was the site of a revolution.

To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing (Barthes)

Free from its author, the art work in the hands of its interpreter is open-ended and forever becoming.

Lost Owl: bezel-set rubies and diamonds, 18ct white gold (London, 2012) (see in store)

Rigorous Discipline IN Indulgent Permissiveness

- the Arts and Crafts' resistance to industrialisation was soon followed by dehumanising Fordist production lines;

- the Constructivist New Spirit of the interwar period ended with the rise of fascism, which brutally crushed the gains made by labour movements;

- many feminist authors argue that the 1960s and New Age did as much harm as good for the women's movement.

Whether one agrees or not with the final claim, today’s world is certainly no “rhizomatic”, non-hierarchical network utopia.

utopian dreams take place, they explode - and even if the actual result of a social upheaval is just a commercialised everyday life, this excess of energy … persists, not in reality, but as a dream haunting us, waiting to be redeemed. (Zizek, Pervert's Guide)

Do we not occupy such a place today? a spiritual desert haunted by unfulfilled dreams of a better world? What should we, can we even, redeem?

Reflecting on the Netflix movie Wind River, Zizek recalls the final scene:

a Native American father (Martin) who has tragically lost his teenage daughter sits, mourning, his face painted. A white friend approaches and asks “what’s with the paint?”. “It’s my death face”, replies the bereaved father who then explains that he taught himself the “death face”. Invented it. No one was left from his tribe to teach him the “real thing”. So he sits, honouring his lost daughter, with (as he himself then says) “shit” on his face.

The Arts and Crafts, in line with the Pre-Raphaelites, wanted to redeem the premodern, naive, “Garden of Eden” Renaissance naturalism. The Constructivists did the same, falling back in more ancient ideas and changing the concept of "nature".

Maybe, rather than reviving some lost purity or perfection, what we need today are more non-ironic and yet bullshit ‘death faces’: talismanic numinousness utterly devoid of any historical content.

Perhaps the post-war modernists knew this. However, there is a balancing-act in their work...

Does the finest brutalist jewellery not balance that rigorous spiritual discipline of careful constructivist architecture and luminosity (Huxely’s Heaven) with that spontaneous - raw and indulgent - permissivity of the surrealists (Huxley’s Hell)?

The next step, then, is obvious: neither a return, nor a balance...

Martin, the bereaved father, positively identifies with (gives presence to) the negativity (absence) of his community’s historical memory. Today we should, like him, realise that there is no garden-of-eden paradise to return to, to fall back on. We can only identify with loss as a positive category.

The only thing to be redeemed, then, is craftsmanship itself. Martin's "death face" - like the X of Malcolm X - is not literal emptiness, but a positive manifestation of the absence of heritage: an authentic spiritual discipline in and from the permissive void left behind by a lost history.

As Zizek himself once said...

What I think we should rehabilitate today is not beauty, but good craftsmanship: art as hard work.

You have to study, to learn how to do it. Craftsmanship: that's what I admire today.

That’s maybe even the truly subversive thing...

The most subversive thing today is to be truly disciplined and do your hard work.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INTRODUCTION

- Barbara Cartlidge - Twentieth-Century Jewelry

- Aldous Huxley - Heaven and Hell (link)

- Geoffrey Munn - Forward (link)

- Slavoj Zizek - Youtube Interview (link)

- Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture

- Toni Greenbaum - Constructivism and American Studio Jewelry, 1940 to the Present

- Aldous Huxley - Doors of Perception (link)

- Sam Kramer: https://www.ganoksin.com/article/sam-kramer-fantastic-jewelry/

Modernism, Take 3

Gerda Flockinger:

- https://www.ganoksin.com/article/gerda-flockinger-lady-british-jewelry/

- https://encyclopedia.design/2024/07/02/gerda-flockinger-pioneering-jewellery-designer-and-educator/

- http://www.johndonald.com/

- Muriel Wilson - REVITALISING JEWELLERY DESIGN: THE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF MODERN JEWELLERY 1890-1961 (JSTOR)

- Goldsmiths: https://www.thegoldsmiths.co.uk/collection-news/john-donald-1923-2023

- Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author: (link)

- Slavoj Zizek - Pervert's Guide to Ideology (link)

- Slavoj Zizek - BLADE RUNNER 2049: A VIEW OF POST-HUMAN CAPITALISM (link)