The Cardinal, the Painter, and the first Antiquarian

In the Palazzo Madama, in a cobbled piazza in the heart of Rome where the ancients had once attended games and gathered together in Emperor Nero’s public baths, lived a Cardinal. He lived modestly for a Medici. That is to say, House Medici - the great Italian banking dynasty - granted him a stipend sufficient for the upkeep of the palace and just fifty well-looked after servants.

History does not only move in one direction. Like a pebble dropped lightly into water, the ripples of seemingly innocent events fan out in all directions and are even amplified, becoming waves which break on the shores of generations past and future.

first, when the local Barberini family - who had militarily resisted the Medici - decided to leave Florence and move to Rome, where they would become a dominant clerical and political force, (more on Barberini later)...

Cardinal Francesco was, one might say, an enlightened man of the faith. Behind the tall arched windows of his three-storey Renaissance Palazzo, the rooms were generously adorned with his collection of ancient sculptures, with vitrines of medals, gems, and cameos. Masterpieces of the great painters - Da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo - brought to his dinner table illustrious guests from across the continent. It was Cardinal Francesco who granted a room in the Palazzo, and an allowance, to a struggling and upcoming painter from Milan - a wayward but astonishingly talented soul - a rogue and a brawler, who the Cardinal hoped no doubt to straighten out, by the name of Caravaggio.

"The Cardsharps" by Caravaggio: the first Caravaggio painting bought by Cardinal Francesco (c.1594)

Piersec saw a vase. And he was astounded.

It was glass, but resembled a layered onyx cameo. The white was cut away into the dark background producing perfect detail, contour and shadow.

The Vase that Peiresc found in the Cardinal’s collection remains to this day today one of oldest and finest works of Roman Cameo Glass in existence.

Possessed by the vase’s beauty - its so perfectly sculpted and complex mythologies - Peiresc immediately had a lead copy of the work sent to one of his favourite correspondents: the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens. Rubens was also in Italy at the time making the acquaintance of another Duke - The Duke of Mantua, of House Gonzaga.

The painter, no doubt stunned after receiving Peiresc’s copy , buried himself among the treasures of his own noble host who eagerly indulged him.

Rubens, perhaps hoping to outdo the Frenchman's discovery, was not disappointed.

The (re)discovery of the Gonzaga Cameo by Rubens would have a profound effect on the painter’s future works.

Peter Paul Rubens himself later wrote...

"I have seen it several times, and have even held it in my hands...

I believe that among cameos with two heads it is the most

beautiful piece in Europe". (letter 123)

The Gonzaga Cameo: Indian Sardonyx; Hellenistic Period, c.300BC.

Agrippina and Germanicus: Rubens c.1614.

And Peiresc and Rubens together would soon set about the mammoth task of cataloguing such artworks - a catalogue of carved gems that the antiquarian and the painter never finished.

The Triumph of Licinius: Sketch of a Cameo by Rubens, likely made for the unfinished catalogue

Lost Owl: Socrates Cameo Brooch, Georgian period, shell; circa 1800 (see in store)

On Monsoon Winds, a. The Greeks

"From the earth comes the tribe of every kind of stone, and they have boundless and multifaceted powers; … a power undecaying and unageing that when they are born their mother hands over to them."

Excerpt from Orphic Lithica (17)

Lost Owl: 19th Century Aurora Fresco Cameo Brooch, shell (see in store)

The Harappa Civilisation, two thousand years before Alexander, sailed on monsoon winds from Northern India to trade with ancient Mesopotamia - modern-day Iran - where Harappa intaglio seals (below) were unearthed in Mesopotamian graves.

Harappan civilization stamp seal (left) ca. 2600–1900 BCE; modern impression (right) - MET

Indo-Mesopotamia trade routes; 3rd millennium BCE

From Mesopotamia across Arabia and into the Mediterranean, these techniques found their way into the hands of the Greeks, for at the same time, - in the third millennium BC - Indian Carnelian from the Indus Valley arrived at the fortified Greek trading hub - the island of Aegina.

The Minoans of Crete, a thousand years later, had preserved this knowledge, carving intaglio seals on hard stones like jasper.

Green jasper, with Cretan hieroglyphs, 1800 BC

With one hand, a craftsman guided a drill. The drill, whose tip was coated in emery powder to cut the hard gemstone, was rotated at speed by the backward and forward motion of a bow in the craftsman’s other hand.

Carnelian scarab engraving (450BC-400BC)

“The drill and bow-string were not tools peculiar to the gem-engraver, but were used in all the arts of carving and sculpture” writes the archaeologist J.H. Middleton.

Another thousand years pass, and in Phoenicia (Lebanon) - 600BC - on the eastern front of the Mediterranean, Indian Carnelian was still being engraved, still using the same, already ancient, technology.

Lost Owl: Carnelian intaglio with depiction of Athena (see in store)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe himself wrote in his "West–Eastern Diwan":

"Carnelian is a talisman, It brings good luck to child and man;

If resting on an onyx ground, A sacred kiss imprint when found.

It drives away all evil things; To thee and thine protection brings.

The name of Allah, king of kings, If graven on this stone, indeed,

Will move to love and doughty deed.

From such a gem a woman gains sweet hope and comfort in her pains."

Hellenistic Intaglios (c.250BC-20BC)

- intaglio representing Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt

- Intaglio with Scene of Aeneas and his Family Escaping from TroyAeneas, son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the goddess Venus, escapes with his family from Troy

In 300BC, the Greek economy flourished like never before - fruit of the slave labour of Alexander’s mining colonies - but the mines of the Aegean brought forth few such magical stones. They were scarce on the Greek Islands.

However, the island of Naxos provided marble for construction, and the largest emery deposits of the ancient world (the second largest even in modern times). Emery from Naxos was used throughout the Mediterranean to construct the tools and to polish the precious hard stones - often carnelian and sardonyx - that still traveled the ancient trade routes from East Asia.

Lost Owl: Georgian spinner fob comprising three agate intaglio carvings of cupid-eros (see in store)

Apocrypha 1: The Line of Barbarians

Early-to-late 1700s

Cornelia Costanza Barberini was the last of that line. Her life’s project was to settle her father’s debts while maintaining her eccentric and luxurious lifestyle (she was a Barberini, after all, and the Princess of Palestrina).

Cornelia achieved this by employing two key strategies:

- An early (12 years old) and tactical marriage to Giulio Cesare of House Colonna which had the two-pronged effect of a) legitimising her position as female heir to the Barberini fortune while b) folding the Barberini titles into House Colonna - good for her, good for her husband;

- The well-timed selling off of pieces from the extensive Barberini collection of antiquities.

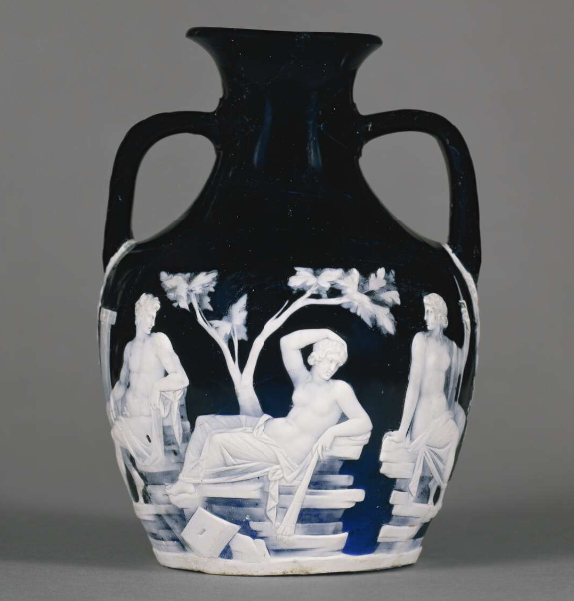

One such piece was a marvellous glass vase - in the ancient style - imitating onyx cameo.

The heirloom had been in her family for almost two centuries; a difficult decision perhaps...

...but in the end, Cornelia was much more about Rococo…

In Cornelia and Giulio's Palazzo Barberini .

Apocrypha 2: From Naples with Love (and carved gems)

mid-to-late 1700s

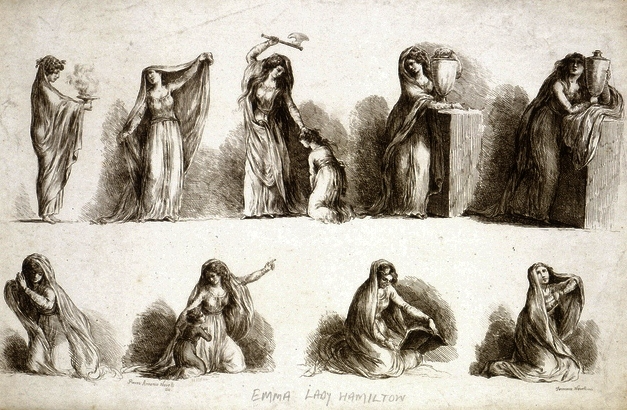

A stone was being sculpted by the waterfront in Naples in a comfortable room of the Palazzo Sessa where, likely after a bottle or two of port, Emma Hart struck a pose.

Rapturous applause.

Her dress had been made to her own specifications, inspired by the common folk of the bay. Another pose, and the guests - many standing, for all the luxurious upholstered red armchairs were occupied - cheered, laughed approvingly, and fought to refill her glass. The blacksmith’s daughter was undaunted by the elegant company she kept: for her suitor’s prestigious milieu, the vulgarity of her manners were exceeded only by her wit, energy, beauty and charm.

Emma Hart's repertoire of poses - Cleopatra, Athena, Helen of Troy, Medea - was a wonderful surprise even to the man, some thirty years her senior and soon to be her husband, in whose Neapolitan Palazzo she now lived and entertained. And why wouldn’t he be impressed?

It was his, Sir William Hamilton’s, collection of antiquities that inspired her performances.

Of course, she had made a name for herself before all that, back in England. George Romney had painted her obsessively, only to abandon her to her fate without a word, pack her and her mother up and send them abroad - here, into the illustrious but unknown world of this new suitor and of more painters painting her…

But life in Naples was growing on her - as was her host...

Having exhausted her repertoire ( “attitudes”, she called them) and after a curtsy, the guests resumed their chatter. Sir William and one of his guests approached her.

“Mr. Marchant, a gem-engraver from England”, announced Sir William.

Another curtsy.

Mr Marchant had, in an ever-so-tiny lump of stone, engraved her portrait. Her little profile, like her performance, was just as Sir William’s antiquities.

Emma Hart, by Nathaniel Marchant

Nathanial Marchant, of his own style, commented: "I have kept the work as light as possible in imitation of the best Greek gems"

Artists and antiquarians back in England had been inspired by Emma Hart’s husband-to-be. Drawing on primary sources, Nathaniel Marchant's biographer Gertrud Seidmann speaks of the "rapid" and "astonishing progress of fine arts in England" at this time. Sir William's publications in the 1760s and 70s Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities had even informed the work of Josiah Wedgewood.

When Emma Hart - marvelling perhaps at her new Neopolitan lifestyle - so proudly wrote...

"The house is full of painters painting me...

All the artists is coming from Rome to study from me" and

"Marchant is cutting my head in stone, that is in cameo for a ring"

... her dear Sir William had already brought a magnificent vase, acquired from a Scotsman, back to England, of which Mr. Wedgewood was making a most convincing copy...

The Barberini Vase, copy by Josiah Wedgewood

"You will be pleased, I am sure, to hear that a treasure is just now put into my hands,

I mean the exquisite Barberini vase with which you enriched this island"

wrote Josiah Wedgwood I in a letter to William Hamilton, June 1786

Lost Owl: Wedgwood blue jasperware plaque with Heracles at Delphi, consulting the oracle Tiresias with Athena stood atop a pedestal entwined by snakes. Set in gold, circa 1850 (see in store)

Intaglios, forever

"The highest sense in narrowest room must fit"

Goethe

Our first cities, our earliest civilisations - five thousand years ago - found ways of penetrating hard stones with tools still harder that they would clearly and effectively leave a discernable mark - a mark of ownership or identity, of authenticity or of spiritual significance.

But one should perhaps think of Cameos, and even Intaglios - in their most exquisite forms - as sculptures, not engravings. .

Lost Owl: Victorian Intaglio ring with oval carnelian panel depicting Hermes (see in store)

If indeed, Sir William Hamilton had introduced Nathanial Marchant to Emma Hart as a “gem-engraver”, either the artist would have corrected him, or at the very least, been mildly insulted. Nathaniel Marchant saw himself as a sculptor, a purist, and successor to an ancient and noble art form in decline.

Before arriving to Naples at Sir William Hamilton’s Palazzo Sessa, Nathaniel Marchant’s studio in Rome was a sensation - he was a hit. Not only English, but local clientele sought his attention - from English lords and ladies, to Roman cardinals and Pope Pius VI, and “People of Distinction" from all over Europe.

His Intaglios were far from mere seal-engraving or the reproduction of monograms and coats of arms - that was a purely practical and repetitive task of an inferior status.

Pope Pius VI - Intaglio from the engraving made by Nathaniel Marchant

But why was Marchant such a hit? Cameos were in vogue, even more so for ladies, while intaglios had the air of a stuffy yet capricious gentleman’s puritanical taste for antiquity.

Where others stuck to and reproduced this trend - even mass-produced in the case of Wedgewood in England - Marchant, a leader rather than a follower, distinguished himself by his dedication to the most ancient and refined of lapidary practices.

According to jewellery historian Gertrud Seidmann, Nathaniel Marchant…

"…imposed his own taste on his patrons, as he gained the respect of both visiting Grand Tourists and British fellow artists in Rome."

His works were not only antique in their subject matter and style, but in concept too. His clients were often represented in their commissions or dedications through complex allegory as choice figures from antiquity.

Marchant’s Hercules Restoring Alcestis to Admetus was presented to The Duke of Marlborough, his patron, an avid collector of Hercules-themed pieces. But Marchant’s choice of subject did not only reflect his patron’s interests, it simultaneously described them and their personal relationship.

Hercules in his efforts and Alcestis in her sacrifice are selfless in deed - selfless as the patron is to the artist - and both are loyal to the Kingdom which, like the arts of antiquity, is something far greater than either.

Marchant’s Nymph and the Swan was dedicated to the Countess Spencer who hosted him on many occasions.

Cameo by Benedetto Pistrucci: Pistrucci made use of Marchant’s Nymph and Swan for this piece in a setting by Castellani

The artist’s assertion, however, that the female character is a nymph (not Leda), is supposedly a reference to stanzas from an epic medieval Italian poem - “Orlando Furioso” - in which “benign white birds” save men’s names from oblivion, and a “lovely nymph” immortalises them in her sacred shrine.

"Some names are saved by means of those benign

White birds, though oblivion every other

Fair name consumes, while that pair divine

Now swim, now beat the air, till they recover

Their place upon the bank of that ill stream,

Below a hill, on which a shrine doth gleam,

Sacred to Immortality; from there

A lovely nymph descends the grassy hill,

To those shores, that sad Lethe’s waters share,

And those bright names, that the dark beaks fill,

She hangs about a statue, high in air,

Upon a column in mid-shrine, where still

They may glow, and eternity outlast:

Consecrated by the nymph, and held fast."

Nathaniel Marchan’s Intaglios (intagliare - to carve) are among the most fascinating exercises in coexistence with our ancient human past and mythology. They deploy technologies of the earliest civilisations as well as their imaginaries to repeat and extend their meanings - to breath contemporary life into their eternal characters.

The key is not the fact that “Hercules restored Alcestis to Admetus”; the key is what Marchant then and we today restore to Hercules as we admire and interpret his act - always and forever on history’s gemstones - restoring the Queen to her Kingdom; and what is restored to the enigmatic nymph in her floating garments whose gentle arm reaches down elegantly towards the white bird.

Necklace with one cameo and 6 Intaglios by Nathaniel Marchant

The Niccolo Intaglio (far left), is unusual by Marchant, perhaps unique

Epilogue

- Cardinal Franceso never succeeded in straightening out Caravaggio’s violent tendencies, and the painter, after killing a man in Sicily, was hunted down by the victim's family. Caravaggio may have died of lead poisoning from a bullet wound.

- Although Rubens and Peiresc never finished their catalogue of antique gemstones, their attempt inspired a mammoth three volume work by another author, several centuries later.

- Nathaniel Marchant, in his later years, ended up dedicating himself to precisely what he had always hated about working in intaglios: he made coats of arms and monograms in the post of His Majesty's Engraver of Seals. But he also made a fortune and left almost half of it to his dedicated maid who had cared for him as his health declined in the years before his death. Marchant was succeeded in the post by the Italian Cameo artist - only recently settled in England - Benedetto Pistrucci .

Lost Owl: Victorian Necklace with Seven Carnelian Intaglios (see in store)

Bibliography

The Cardinal, the Painter, and the first Antiquarian

- The Letters of Peter Paul Rubens, RUTH SAUNDERS MAGURN, Harvard University Press (1955)

-

Peiresc, Rubens, and Visual Culture Circa 1620, PETER N. MILLER, Brepols Publishers

- The Portland Vase: The Extraordinary Odyssey of a Mysterious Roman Treasure, ROBIN BROOKS, HarperCollins (2004)

On Monsoon Winds, a. The Greeks

- Lithika: On Stones, JOSHUA FINCHER, (2024).

- ECONOMY OF ANCIENT GREECE (link)

- Art of the First Cities, JOAN ARUZ, Metropolitan Museum, New York, Yale University Press (2003)

- The Engraved Gems of Classical Times, J.H. MIDDLETON, Cambridge University Press (1891)

- The Curious Lore Of Precious Stones, GEORGE FREDERICK JUNZ (1958)

- Western-Eastern Divan, JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE

Intaglios, forever

- NATHANIEL MARCHANT, GEM-ENGRAVER 1739-1816, Gertrud Seidmann, Robert L. Wilkins The Volume of the Walpole Society, Vol. 53 (1987)

- Nymph and Swan, Metropolitan Museum catalogue entry (link)